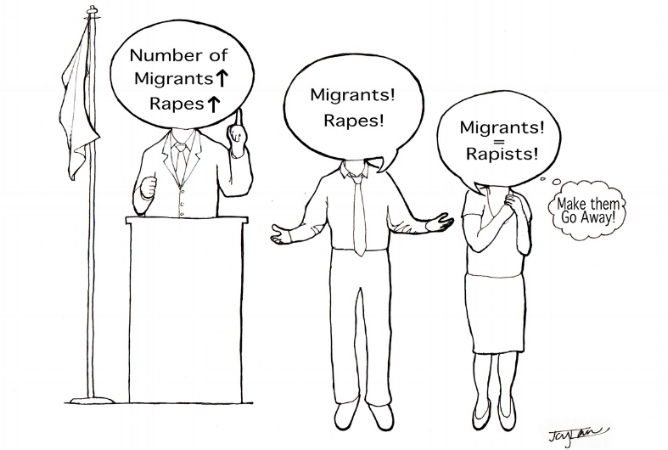

Illustration by Joy Lau, from Talk Decoded [1]. Used with permission.

How does the way we frame news intersect with the world of politics? To learn more, we talked to the team behind Talk Decoded [2], a blog about the power of language in politics: expert in media, politics, and communication Anna Szilagyi and cartoonist Joy Lau.

In Hungary's Great Anti-Migrant Campaign, [3] for instance, Szilagyi and Lau explore the 2016 Hungarian referendum on migrant relocation, looking at framing language such as “Brussels Bureaucrats” and “illegal immigrants.” We used this example as a way to get their perspective on the power and challenges of framing.

Global Voices: How do you define “frame” or “framing”?

Anna: I’m interested in the power of words in politics. I rely on a linguistic conceptualization of framing [4] developed by George Lakoff. According to him, frames are mental structures that can be activated by words. If we hear a word, it will evoke a frame in our mind. As this is largely an automatic process, politicians and the media can influence us through framing effectively without us being aware of it.

Global Voices: Can you give us an example?

Anna: Sure. Since 2015, in response to the implications of the global migration crisis for Europe and the European Union’s plan to resettle refugees [5] among its member states, the right-wing populist government in my native Hungary has been running large-scale propaganda campaigns against different groups and individuals.

Hungary’s government has aimed to set the country’s residents against the refugees, for instance. Various rhetorical tools have been utilized for this purpose, including framing. The vocabulary of the Hungarian propaganda (“danger”, “danger of terrorism”, “no-go zones”, “rapes”, “epidemics”) has merged facts which were taken out of context with lies, as well as blurred the difference between “migrants” and “terrorists.”

These words could evoke the frame of a “state of emergency” in people’s minds, creating the false impression that the refugee crisis brought complete lack of order, chaos, and even lawlessness for Europe.

At the same time, words that could activate the frame of humanitarianism (“shelter,” “food,” “protection,” “family reunion,” “children”) were completely absent from the language of the Hungarian propaganda. The lack of vocabulary that could activate the humanitarianism frame has also supported the spread of the government’s agenda.

Joy: Our first article for Talk Decoded addressed the 2016 campaign by the Hungarian government to influence the vote for the EU plan to resettle refugees. In particular we used and analyzed the material from the government’s campaign brochure. Thanks to Anna’s translation and explanation, I was introduced to the myriad ways in which certain terms were used to instill prejudice against the refugees.

For this set of cartoons, in order to emphasize that real people are being influenced, I drew figures with realistic-looking bodies, but with “bubble heads” to show their thought response to the propaganda words.

You can see in the cartoon above the Hungarian government’s linking of two words – “migrants” and “rapes” – in addressing the refugees. First, they referred to the refugees as “migrants”, which can be construed as a derogatory term, with connotations of temporary residency and a lack of belonging to society. They then connected an increase of “migrants” to an increase of rapes, suggesting that migrants are rapists. Framing, in this example, is used to instill a fear of refugees in the public.

Global Voices: We’re going to assume that you think it’s important to understand framing, given your work in this area. But why is it important, and/or what are the challenges right now?

Anna: Framing can influence our thinking in a subtle way that can mislead us or even be dangerous. I believe that framing is so important that it should be taught as early as in primary school. We use language all the time, yet, most of us has a very limited understanding of how it works. And, oftentimes, journalists are no exception.

I see this lack of knowledge as the major challenge. Framing is not new but today we are basically bombarded by frames through the mainstream and social media. And our lack of knowledge makes us extremely vulnerable to manipulation.

Global Voices: Are there things you think that average news readers and writers could be doing when it comes to frames?

Anna: I think the first thing to ask is how can those who understand the significance of framing because of their work share their knowledge. The NewsFrames at Global Voices is a valuable initiative to educate the public about framing. Within Words Break Bones (see below), we aim to teach framing both to laypeople and professionals, including journalists and experts.

If you are aware of framing, you can always consider the vocabulary that you or others use. You can stop for a second and ask yourself a few questions. What kind of ideas can this word activate in people’s mind? Is this word or frame sufficient enough to describe complex realities? By using this word, will I or someone else contribute to more or less knowledge?

Global Voices: Can you tell us a little more about yourselves?

Anna Szilagyi, reprinted with permission.

Anna: I’m a journalist turned scholar who explores how politicians and the media shape and manipulate people’s ideas and actions through language across the globe. My educational program, Words Break Bones [6] aims to provide children, teenagers, and adults with crucial linguistic skills to identify and counter abusive, discriminatory, and deceitful communication practices in private and public life. I’m also a professor of communication at the Savannah College of Art and Design in Hong Kong. In many of my recent projects, I collaborate with an amazing artist, Joy Lau.

Joy Lau, reprinted with permission.

Joy: My name is Joy Lau, and I am a cartoonist and former architect. In Talk Decoded, my illustrations aim to provide visual summaries for the complex topics in each article. I have always been aware of the power of language, but working with Anna has revealed to me clearly the methods in which language is used to influence others – and there are many examples of this power used in an abusive manner.

I also have an online comic book series, Lonesome Cowgirl Comics [7], that touches on various themes such as Mexican-American inter-generational strife along the southern border of America, and feelings of displacement in a large city such as Hong Kong. I also play the accordion, slide whistle, music box, and my new all time favorite, a train whistle.

Global Voices: By the way, where do you live and what languages do you speak? We are an international community and love to know the contexts from which people are speaking.

Anna: I divide my time between two cities that I love and admire, Budapest and Hong Kong. As for languages, I’m a Hungarian-Russian bilingual. I also speak English as well as a little German and Mandarin.

Joy: I live in New York City. I am most fluent in English and Cantonese.