[1]

[1]Sabino Gualinga, elder of the Sarayaku people, beginning ritual in event of the public apology from the Ecuadorian state. Picture by @wambraradio Medio Digital Comunitario [1], used with permission.

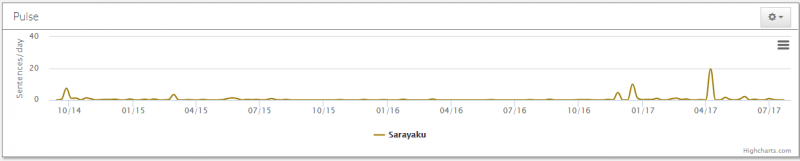

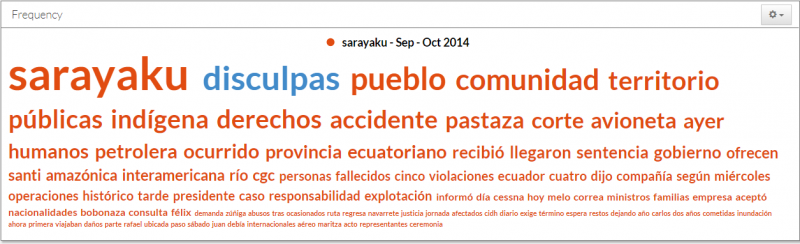

The Sarayaku [2] people, a small indigenous community in eastern Ecuador, are rarely in the news. They live near the Amazon rainforest in Ecuador. But twice in the past several years, they have grabbed the attention of Ecuadorian national media.

Saying “sorry” to the Sarayaku: Tracking down an apology

Between September and November 2014, the Sarayaku burst into public view. The Ecuadorian government had issued a rare apology for allowing mining companies to exploit Sarayaku land without permission.

We dug into the news to reconstruct the larger story. In our Media Cloud search, there are some 204 stories with “apologies” in connection with the Sarayaku community. However, the story behind the apology remains unclear unless one is familiar with the political and legal struggles of the Sarayaku.

As it turns out, the apology [3] was a result of a ruling from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR). The ruling [4], which was issued on June 27, 2012, condemned the Ecuadorian State for violating Sarayaku rights to communal property.

[5]

[5]MediaCloud exploration of words associated with Sarayaku from September through October 2014, in the NewsFrames Ecuador collection. “Disculpas” (apology) is highlighted.

Since the 1980s the Sarayaku have publicly fought [6] against oil drilling on their land. In the late 1990s the Ecuadorian government granted a concession to an oil company for mining Sarayaku ancestral lands, in contravention of law that requires consent from indigenous communities prior to granting mining licenses.

When apologizing in the name of the Ecuadorian state, Minister of Justice Ledy Zúñiga stressed that human rights violations occurred during the previous governments of Jamil Mahuad [7] (1998-2000) and Lucio Gutiérrez [8] (2003-2005).

Ofrecemos disculpas por la violación a la propiedad comunal indígena, violación a la identidad cultural, violación del derecho a la consulta, por haber puesto gravemente en riesgo la vida e integridad personal y por la violación a los derechos de las garantías judiciales y protección judicial y los derechos humanos”, declaró Zúñiga [9].

We apologize for the violation of indigenous communal property, violation of cultural identity, violation of the right to consultation, having seriously endangered life and personal integrity and for violation of the rights of judicial guarantees and judicial protection and human rights”, declared Zúñiga [9].

The apology [10] is a rare political and media victory for the Sarayaku people, and for indigenous groups and activists who mobilize against oil exploration. They extracted a positive judgment from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. They also benefited from broad media coverage of the apology, which was widely broadcast in both Spanish and Kichwa.

Kidnappers or Detainers? A framing victory

After the spike in coverage following the ruling, the Sarayaku people disappeared from Ecuadorian media agenda. In December 2016, stories about the community resurfaced.

The reason? On December 19, through its official Facebook page, Sarayaku, defensores de la selva [12] (“Sarayaku, defenders of the jungle”), the Sarayaku reported that they were holding 11 Ecuadorian Army soldiers who were in their territory without permission.

Most of the Ecuadorian media, including some pro-government media, covered the story by reference to Facebook, without including official statements from the army or government. Initial statements from the Sarayaku on Facebook claimed that the soldiers were “invited to a dialogue [13]” after entering their territory without permission and also that the soldiers were “under the protection [14]” of the community.

[15]

[15]Post on Facebook with which the Sarayaku announced the retention of soldiers in their community.

Later that evening, Ecuador's President Rafael Correa described the incident differently, as one of “kidnapping”. In the following speech, he declared on national media:

esto es inconstitucional, es detención arbitraria, esto es secuestro porque todo el que permanezca dentro del territorio sin hacer nada ilegal se le respeta la libre movilidad.

this is unconstitutional, arbitrary detention, this is kidnapping because everyone who stays inside the territory without doing anything illegal must have free mobility respected.

The government version later reproduced [16] in mass media also claimed that the Sarayaku were breaking the law, and the soldiers were kidnapped (los soldados fueron secuestrados). Throughout the week, the word secuestrados (kidnapped) was only used by the media to quote [17] statements from President Correa or the minister of defense Ricardo Patiño [18].

Most media coverage gave prominence to the Sarayaku version, using the word retenidos (detained) instead of secuestrados (kidnapped) and referring to the extraordinary [19]militarization in the region. In spite of the president's statement, the Sarayaku narrative prevails.

[20]

[20]MediaCloud comparison among words “retenidos” (detained) using by the indigenous leaders and the word “secuestrados” (kidnapped) used by the government, following the incident of the detention of 11 soldiers in the Sarayaku community. December 2016.

When the soldiers were released after negotiations, the word retenidos (detained) used by the indigenous leadership prevailed in the news over the word secuestrados (kidnapped). Both print media and TV and even somewhat pro-government digital media opted for retenidos.

And in the end, even this press release [21] from the government agency Secretary of Communication (SECOM) employed the language of the Sarayaku, saying

así como hay derechos también hay obligaciones que deben ser respetadas para asegurar esos mismos derechos como por ejemplo el de la libre movilidad en el territorio nacional. Por ello el Gobierno rechaza categóricamente la retención contra la voluntad de once soldados de las Fuerzas Armadas por decisión arbitraria de algunos dirigentes de la comunidad Kichwa Sarayaku.

Just as there are rights there are also obligations that must be respected to ensure the same rights as, for example, free mobility in national territory. For this reason, the Government categorically rejects the detention of eleven soldiers of the Armed Forces by the arbitrary decision of some leaders of the Kichwa Sarayaku community.

These moments on the media coverage of Sarayaku people reflects small but important achievements. As Andrés Tapia — communication lead of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon (CONFENIAE [22]) in Ecuador — said, “it is important to acknowledge that, of course, there is conflict, fight, resistance, but there are achievements as well [23].”

* * *

MediaCloud search found just 20 stories in Ecuadorian national media reporting on the incident of detained soldiers. These stories are collected in this online [24] spreadsheet [24], where readers can see that retenidos [25] was used in 14 stories, while the secuestrados was used in 10 stories. The news outlets included in the MediaCloud output are representative of Ecuadorian major media. The search found stories from three of the four major newspapers, including the government-run El Telegrafo [16]. MediaCloud also captures stories from major TV channels [25]. Among the most important Ecuadorian news outlets that reported on the release of the soldiers, Media Cloud results missed a story by “El Comercio” that we found by looking in the newspaper archives. In that story, “El Comercio” used the secuestrados in the headline when reporting on a Minister of Defense announcement [26], but refer to the Sarayaku version in the lead paragraph, using the word retenidos.