[1]

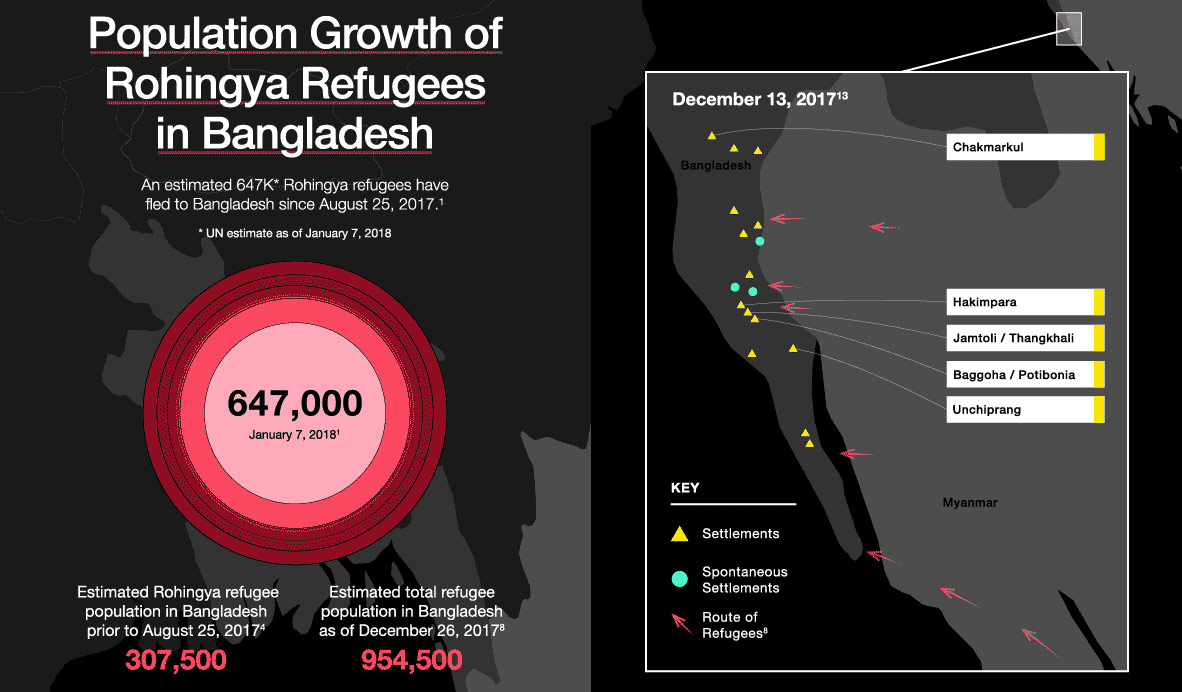

[1]Map showing the growth of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh via UNrefugees.org. Image widely distributed (original sources [1] [2] [2] [1]).

Despite its tropical climate, there seem to be a number of icebergs in Myanmar. In September 2017, National League of Democracy leader and State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi blamed [3] “terrorists” for “a huge iceberg of misinformation” regarding the violence in western Myanmar that, according to the United Nations, [4] has forced more than 688,000 Rohingya refugees [5] into neighboring Bangladesh. At the same time, human rights groups said [6]that reported incidents of Myanmar's militia groups, local security forces and army [7] involvement in the Rohingya Muslims situation were just the “tip of the iceberg”.

So, how do we dive below the surface? In this WordFrames [8] post, we explore the tricky and complicated media conversations [9] around insurgents and terrorists in reference to the Rohingya, specifically members of the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, from Myanmar.

Who are the Rohingya and the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA)?

The Rohingya are a religious and ethnic minority community in Myanmar. The UN has called them the world’s most persecuted [10] minority group, describing the violent acts committed by Myanmar’s authorities against the group as “ethnic cleansing [11]“.

According to researcher and senior fellow at Georgetown University Engy Abdelkader, [10] this pattern of persecution goes back to 1948 when the country achieved independence from their British colonizers:

The British ruled Myanmar (then Burma) for over a century, beginning with a series of wars in 1824 [12].

Colonial policies encouraged migrant labor in order to increase rice cultivation and profits. Many Rohingya entered Myanmar as part of these policies in the 17th century. [13] According to census records [12], between 1871 to 1911, the Muslim population tripled.

The British also promised the Rohingya separate land – a “Muslim National Area [13]” – in exchange for support. During the Second World War [14], for example, the Rohingya sided with the British while Myanmar’s nationalists supported the Japanese. Following the war, the British rewarded [14] the Rohingya with prestigious government posts. However, they were not [13] given an autonomous state.

After independence (1948), the Rohingya asked for the promised autonomous state, but officials rejected their request. Calling them foreigners, they also denied them citizenship.

These animosities continued to grow. Many in Myanmar saw the Rohingya as having benefited from colonial rule. A nationalist movement and Buddhist religious revival further contributed [14] to the growing hatred.

This history is the backdrop to the more recent conflicts in the Rakhine state [15] where the mostly-Muslim Rohingya people have faced persecution. Previous military operations — like Nagamin (1978) [16] and Pyi Thaya (1991-1992) [17] — were recorded in the area as well as more recent conflicts between Buddhist and Muslim ethnic groups in the region going back to 2012 [18] and 2013. [19]

The current situation, which began in October 2016, [20]marked the beginning of the ongoing conflict with the group known as Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), which [21] operates out of Rakhine State and claims to be acting on the behalf of Myanmar's Rohingya. Coverage of the situation inextricably includes mentions of ARSA.

The International Crisis Group (ICG)'s report on ARSA, released [22] on 15 December 2016, says that the group was led by Rohingya people living in Saudi Arabia. Although ARSA or its official name of Harakah al-Yaqin (“Faith Movement”) has ties to some jihadist groups, according to the ICG's report, its stated goal is not jihad but to stop the persecution of Rohingya:

It has called for jihad in some videos, but there are no indications this means terrorism.

However, an ARSA spokesman countered this, telling the Asia Times newspaper [23] that it had no links to jihadist groups and only existed to fight for Rohingya people to be recognized as an ethnic group.

On 25 August 2017, ARSA initiated an attack [24] on Myanmar military, which resulted in the group being declared as a terrorist group [25] by Myanmar's Anti-Terrorism Central Committee, in accordance with the country's counter-terrorism law.

The declaration encouraged official government mainstream media outlets to use [26] the word terrorist directly referring to ARSA, while few independent moderate media like Frontier Myanmar chose [27] to describe them as militant.

How is the English-speaking world talking about the Rohingya situation?

When it comes to English-language news about the Rohingya, insurgency rather than terrorism seems to characterize the coverage.

To begin our exploration, we used the Media Cloud data analysis tool (see box) to search for topics surrounding the family of words used in reference to the Rohingya in US-oriented media between Feb 6, 2017, and Feb 6, 2018. Given the dominance of US Media for English-speaking markets, we chose US-oriented collections as proxies for conversations in the larger English-speaking world.**

What is Media Cloud?

Media Cloud [28] is an open source platform developed by the MIT Center for Civic Media and the Harvard Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society. Media Cloud is designed to aggregate, analyze, deliver and visualize information while answering complex quantitative and qualitative questions about the content of online media.

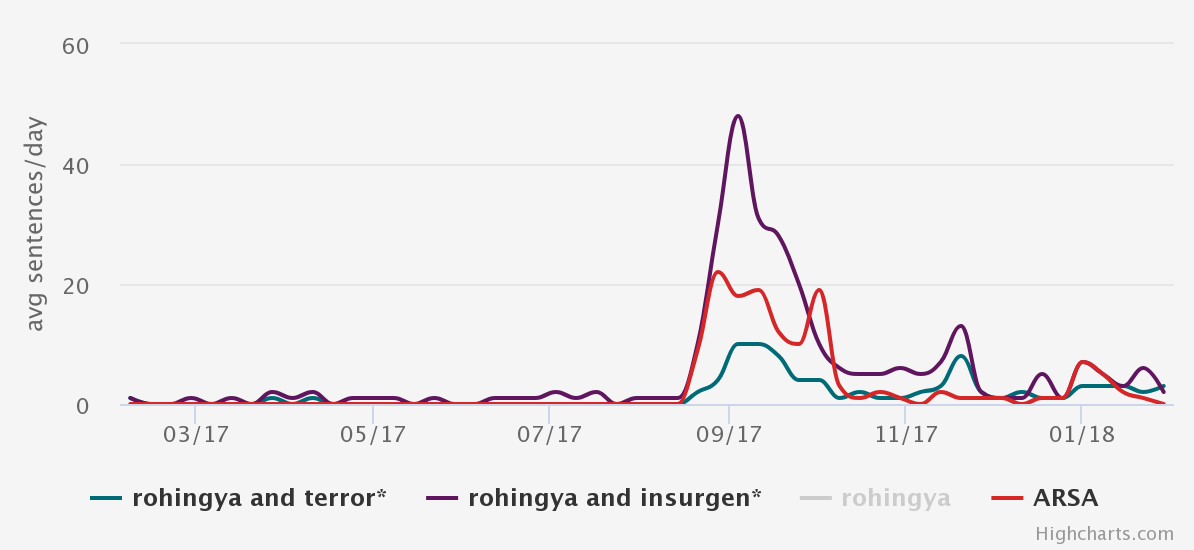

Using the MediaCloud Explorer, we found a pair of dominant terms that appeared frequently in the same sentences with Rohingya: terrorist and insurgent. Media Cloud located 6,323 stories and related texts in the US collections with the word “Rohingya,” with 1443 stories and comments related to the root insurgent* and 499 stories and comments related to the root terror* (captured 27 March 2018).

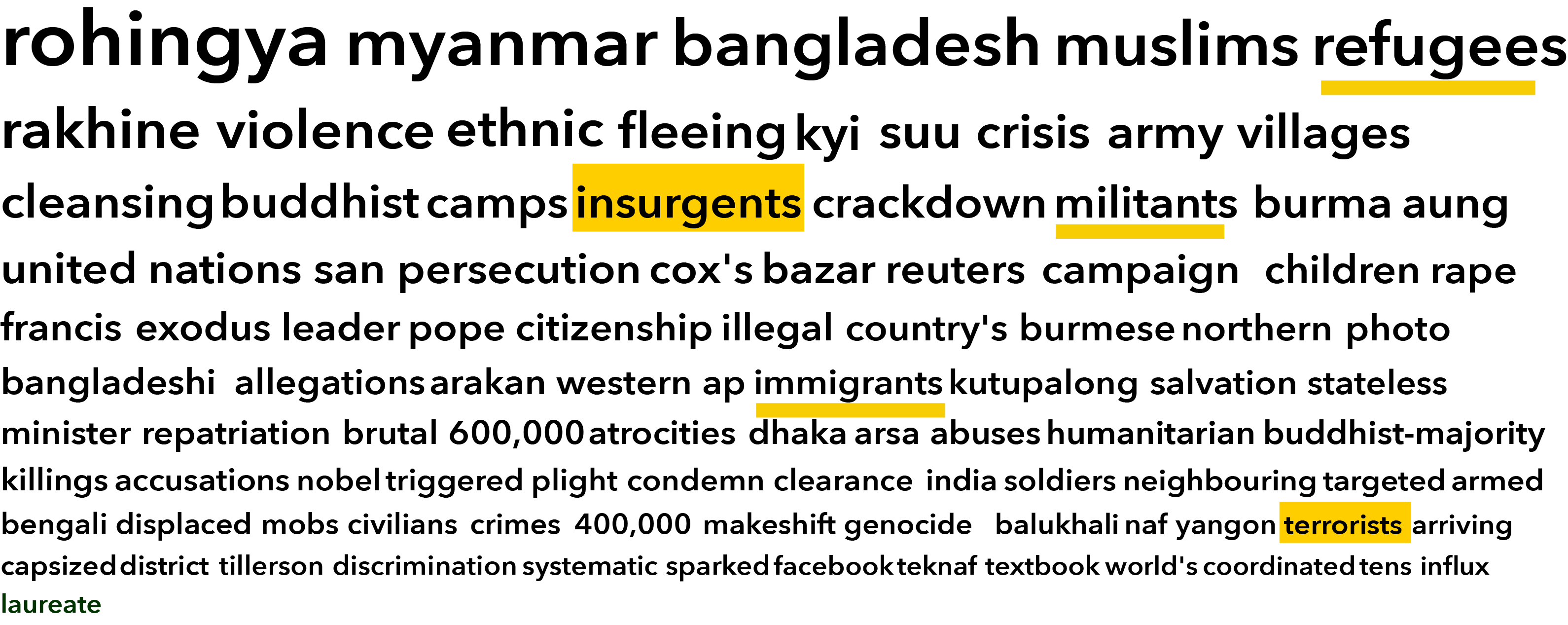

Prevalent terms in stories containing “Rohingya” in US collections from February 2017 – 2018 with characterizations highlighted. Source: Media Cloud (view larger image [29])

The dominance of the terms related to insurgent versus terrorist in the sample is more than two to one:

Frequency of stories related to insurgent or insurgency (purple) and terror (green) in the “Rohingya” results during the search timeframe. Frequency of stories mentioning “ARSA” (red) are also included. Source: Media Cloud (view larger image [30])

When digging deeper into stories with the word terrorist, rather than being directly used, the term often appeared within quoted statements or between quotation marks.

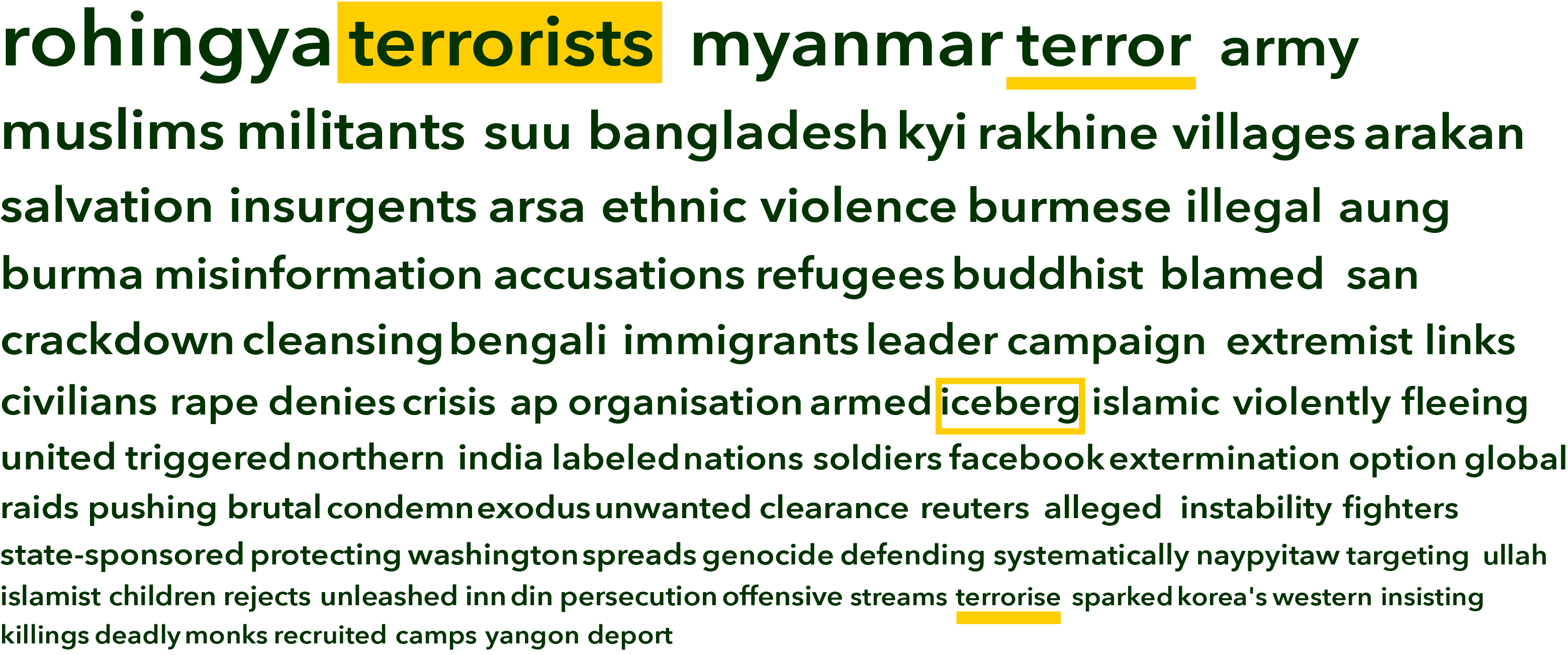

Prevalent terms in stories containing “Rohingya” and “terror*” in US collections from the February 2017 to 2018 period. Source: Media Cloud (view larger image [31])

For example, in this [32] CNN article, answering 5 questions about ARSA, the word terrorist appears only quoted in a government statement about ARSA:

The Rohingya militant group known as ARSA has since proposed a ceasefire to allow aid groups to respond to the humanitarian crisis, which the government has rejected, saying it doesn't “negotiate with terrorists.”

And in this one [33] we see the word terrorist between quotation marks:

Atah Ullah insists that al-Yaqeen are not “terrorists”, saying they will never attack civilians.

While this AP post [34] quotes Myanmar's government describing ARSA as “extreme Bengali terrorists”:

After the latest attacks, Myanmar’s government has insisted they should only be referred to as “extreme Bengali terrorists.”

Yet coverage using the term insurgent or insurgency was more direct:

Prevalent terms in stories containing “Rohingya” and “insurgent*” in US collections from the February 2017 to 2018 period. Source: Media Cloud (view larger image [35])

Thousands of Rohingya flee ‘no man's land’ after resettlement talks [36]

February 18, 2018. Reuters.

“Nearly 700,000 Rohingya fled Myanmar for Bangladesh after insurgent attacks on Aug. 25 sparked a military crackdown that the United Nation as has said amounted to ethnic cleansing, with reports of arson attacks, murder and rape.”

The Daily Mail refers to 25 Aug events in all related articles as “insurgent attacks”:

Bangladesh gives names to Burma to begin Rohingya repatriation [37]

February 18, 2018. Mail Online.

“The violence erupted after an underground insurgent group, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, attacked security outposts in Rakhine in late August.”

And in this Indian Express article, ARSA is introduced as “an armed militant group”:

Myanmar’s armed Rohingya militants deny terrorist links [38]

March 29, 2017. The Indian Express.

“In October last year, armed men killed nine Myanmar border guards, triggering a savage counterinsurgency sweep by the army in the Rohingya area of Rakhine.”

Even exploring articles with the mention of “ARSA” alone finds an overall struggle over characterizing the group as “terrorist” versus “insurgent,” with one Media Cloud sample over the year period returning 99 sentences with “ARSA” and “terrorist” versus 84 sentences with “insurgent”.

Prevalent terms in stories containing “ARSA” in US collections from the February 2017 to 2018 period. Note the similar frequency of “terrorist” related to “insurgent.” Source: Media Cloud (view larger image [39])

Based on reading some of the articles that Media Cloud returned, one reason for the preference of “insurgent” over the term “terrorist” seems to come down to the response of some Rohingyans to the actions of Myanmar security forces and local militia in the larger context of a humanitarian crisis.

For example, in a conscious or unconscious attempt to balance the representation of the main actors in these events, this September 2017 Washington Post piece [40] introduced the situation in Myanmar by describing the Rohingya as “being terrorized by Burma’s military, together with Buddhist villagers, using a pretext of rooting out Islamist insurgents“ in its introduction.

Almost two months later, in another story [41] by the Washington Post, the author talks about the acts of violence committed by ARSA against Burmese and Bangladeshi Buddhists, using the words insurgent and militant throughout the article to describe the group.

The Classification of Terror

Despite the government's declaration of ARSA as a “Terrorist Group”, ARSA responded with a statement of their own soon after stating that, in fact, it was the state itself that was guilty of terrorism:

STATEMENT: #ARSA [42] declares “#Burmese [43] Military Regime” as a “Terrorist Org” causing terror and destruction to ethnic #Rohingya [44] population. pic.twitter.com/dQerzIbfZO [45]

— ARSA_The Army (@ARSA_Official) September 3, 2017 [46]

This led to some additional digging on our part: when exactly does an event get categorized as “terrorist”? According to the Global Terrorism Database (GTD), there are 430 incidents related to the Rohingya [47] through late 2016.

Yet none of these events are with the state as the perpetrator, and that is intentionally so. The Global Terrorism Codebook [48] defines a terrorist attack as the “threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by a non-state actor to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation” [emphasis added]:

3. The perpetrators of the incidents must be sub-national actors. The database does not include acts of state terrorism.

The Global Terrorism Database does address overlaps between terrorism and other forms of crime and political violence such as insurgency. For example, this action by Shan State Army – North [49] in November 2015 was classified as “Insurgency/Guerilla Action.”

Trying to delve into the difficulties of classifying insurgency or guerilla action against insurgency, researchers Erin Miller, Gary LaFree and Laura Dugan went further in their book [50], isolating how the factors of time and space can also have an impact:

If terroristic violence became really sustained and extensive in an area—if it was no longer fitful or sporadic—the activity was generally no longer called terrorism, but rather war or insurgency.

Or, consider this classification: among the events monitored by the Global Database of Events, Language, and Tone (GDELT) associated with Myanmar military in recent months, you can find 120 counts of “Unconventional Mass Violence” in its collection.

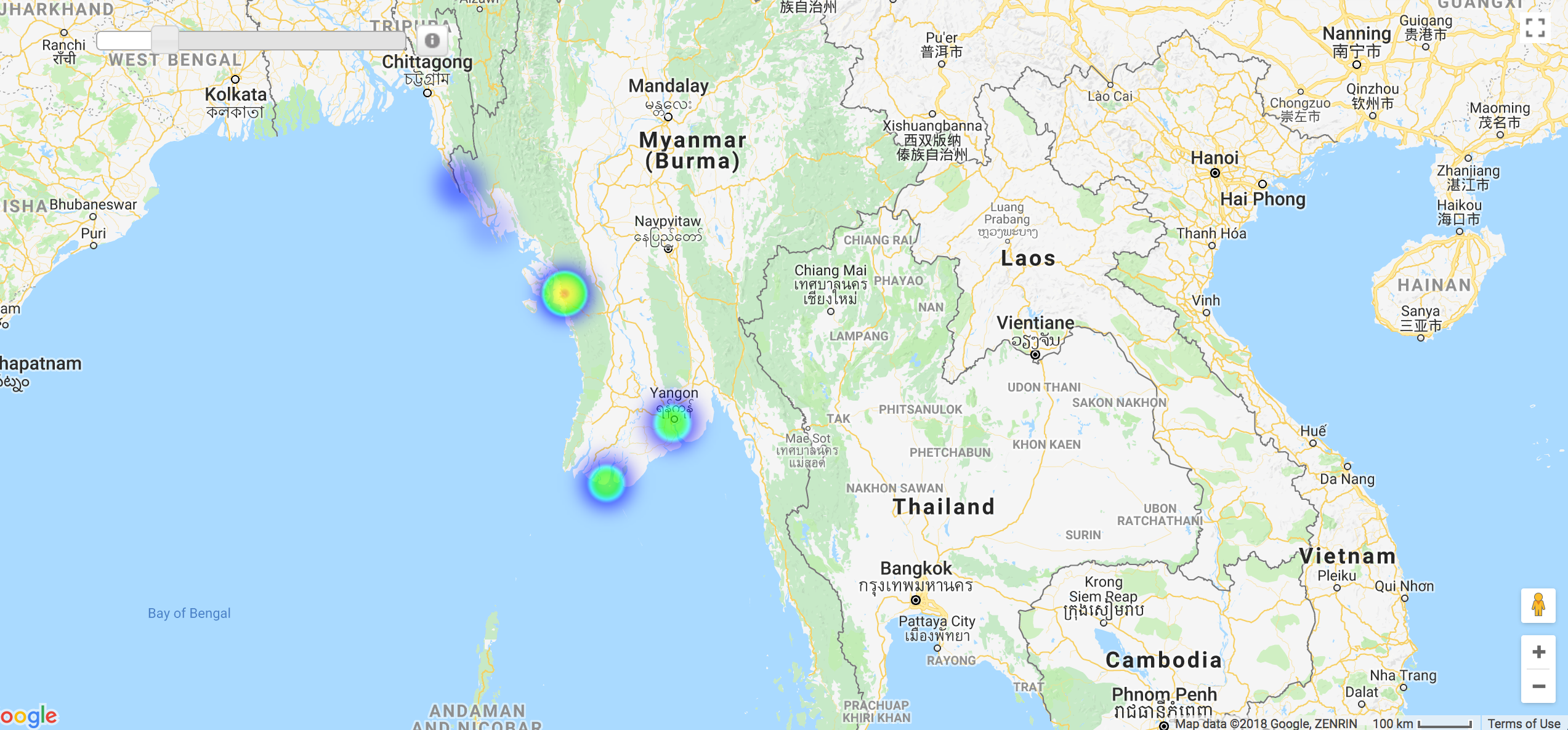

Global Database of Events, Language, and Tone (GDELT) Heatmap Visualizer of Events from 6 April 2016 to 2 May 2018 initiated by Myanmar Military, classified as type 20 “Use Unconventional Mass Violence (20)” (original visualization [51])

This small foray into the exploration of English-language news stories related to the Rohingya is just “the tip of the iceberg” — there are many questions about the quality and diversity of news coverage that need to be asked and answered.

But perhaps, for now, we have seen enough to simply conclude that in this battle over terms, and ultimately in certain situations of crisis, struggles over language represent larger struggles over framings. In this case, there is a struggle between the Myanmar government's characterization of events versus ARSA's. And this struggle — in which an estimated 647,000 Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh between 25 August 2017 and 7 January 2018 [UN Refugees, per top graphic] — also shows to some extent where language ultimately fails.

Other Readings from Global Voices:

- Lone Wolves Are ‘Terrorists’ Too [52]

- When a Picture Is Worth a Thousand Wrong Words [53]

- Terrorist. Rebel. Illegal Immigrant. What's in a Name? [54]

Connie Moon Sehat [55] contributed to this article. The author wishes also to thank Andrea Brás [56] and Thant Sin [57] for their help.

**English-language media based in Myanmar may be struggling over slightly different terminology — militant (rather than insurgent) and terrorist — (as this Media Cloud search [58] in one of the NewsFrames collection reveals); militant also seems to be more frequently used than terrorist. For the scope of this story, we do not undertake a thorough review of these preliminary results.