“21/09/08, Journées européennes du patrimoine Portes ouvertes intégrales à la DDC [Demeure du Chaos]” Image by Flickr user Thierry Ehrmann (CC BY-2.0)

We thought we'd take a closer look at recent French-language news and blogs to discover more about this complex word.

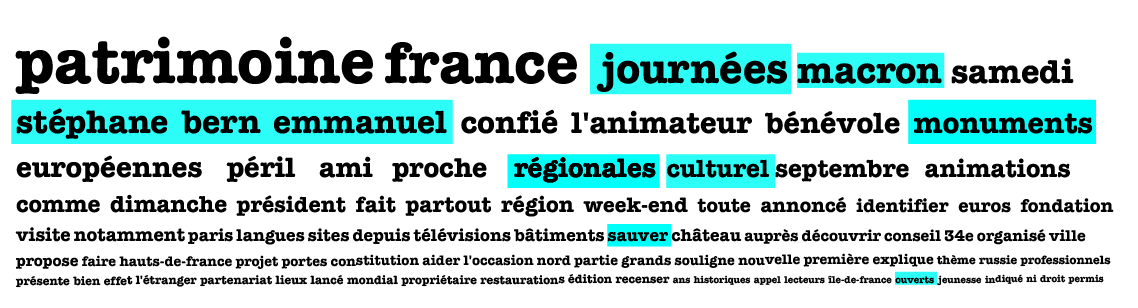

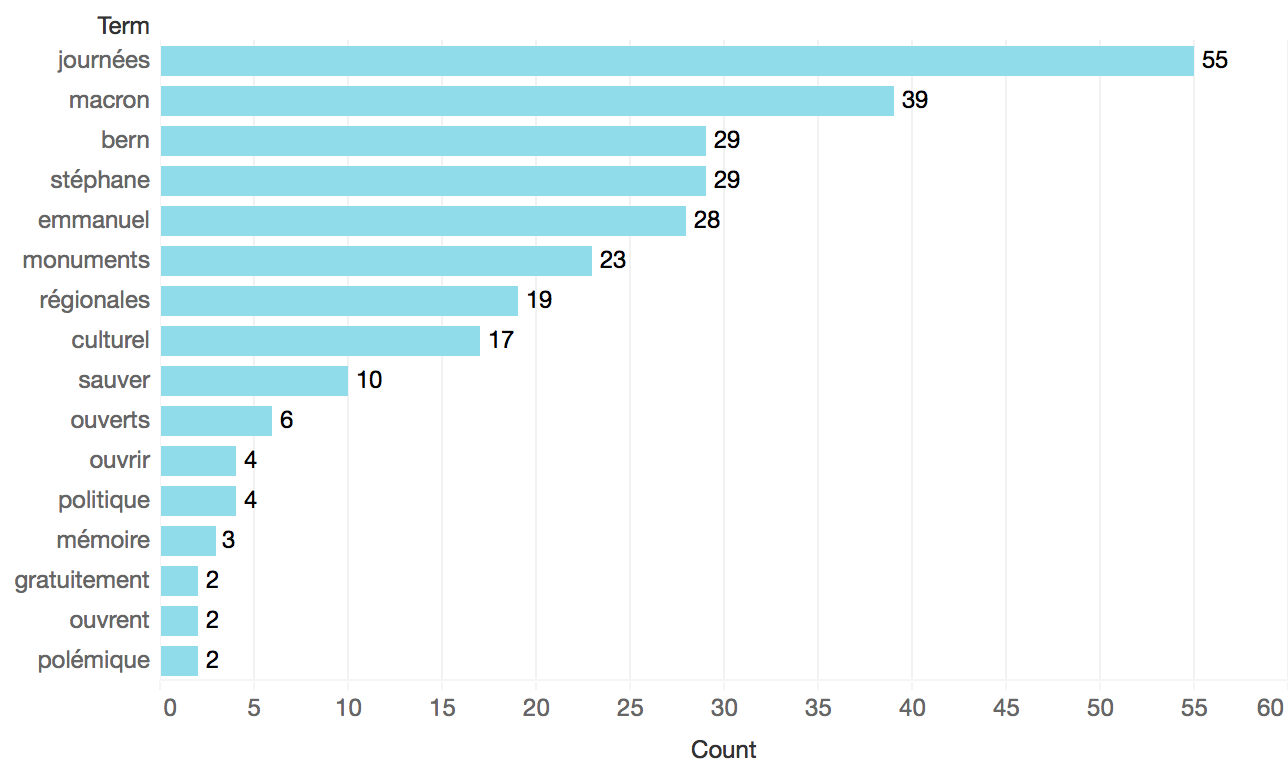

A sample of frequent words associated with patrimoine and culture in French-language news and blogs between Sept. 5 to Oct. 5, 2017. Source: Media Cloud (View larger image)

As it happens, our search of articles appearing between September 5 and October 5, 2017 coincided with a yearly series of cultural events and a political controversy. These two factors—both things of which French media is always fond—meant that our search results focused less on some of the other senses and meaning of the word patrimoine, including wealth and property.

Patrimoine as culture

Many of the articles we found that addressed these themes were the result of an annual ritual called Journées européennes du Patrimoine (European Heritage Days), that took place on September 16-17. This event, which started in France in 1984, is the equivalent of Doors Open Days in Anglo-Saxon countries. The idea spread to other places in Europe, until the project was internationalised under the Council of Europe in 1991. 2017's “Days” attracted a total of 12 million visitors.

Events included everything from local outings to unusual spectacles:

- CRAZY HORSE, AND.. (Crazy Horse, asile et Cluedo géant… nos 10 insolites des Journées du patrimoine)

FranceInfo:, 15 September

From the Saint-Anne psychiatric hospital to the legend of the Dame Blanche, the Crazy Horse cabaret and a police investigation in the middle of the Jura vineyards, the Journées du patrimoine are also an opportunity to discover original places and amazing activities.

Heritage, perhaps unsurprisingly, also has to do with monuments. One example among thousands can be found south of Paris where the “lovely” domain of Sceaux and its beautiful château, grounds and gardens, awaits visitors.

- VIDEO. HERITAGE IN ILE-DE-FRANCE: A LOVELY LEAP IN THE PAST (Patrimoine en Ile-de-France : un joli Sceaux dans le temps)

Le Parisien, September 8

A few days ahead of the launch of the must-attend exhibition dedicated to Picasso, zoom in on this lovely domain in Hauts-de-Seine with its rich past from Colbert to today.

But patrimoine-related monuments don't have to be locations. Consider this episode from aeronautical history: the 1953 “Super Constellation”, whose restoration operation took several years.

Whatever the age, heritage needs to be preserved and accessible (which sometimes means free entry (gratuitement). This ancient Greek quarry in Marseilles, a city rich in archaeologic remnants, saw citizens and activists mobilize against a big real estate project encroaching upon the site. Saving (sauver) a piece of heritage may also lead to creative initiatives, like “Adopt a Castle” :

- ADOPT A CASTLE IN PERIGORD FOR 50 EUROS: AN INCREDIBLE BET ABOUT TO BE WON (Adopter un château pour 50 euros en Périgord : le pari incroyable en passe d’être gagné)

Sud Ouest, 19 September

Adopt a Castle achieved its goal of collecting 500,000 euros, thanks to 6,000 co-owners. It's planning to buy Paluel on Thursday in Bergerac.

The terms in the sample that we explored further for this Culture Shot. Source: Media Cloud (View larger image)

Patrimoine as local and national politics

Celebrations in September focused not merely on national memories, but very much highlighted the strong regional and sometimes legal dimension of the idea of patrimoine. Consider this court battle over the naming of baby Fañch. Fañch, a name of Breton origin, was refused as legitimate for registration by the civil registry service because of the tilde above the “n”.

Arguments on behalf of the baby's parents appealed to heritage:

(…) dès lors que les langues régionales appartiennent au patrimoine de la France, il conviendrait au contraire d'en tirer les conséquences. Or, en interdisant le tilde breton, “la circulaire de 2014 provoque une dégradation de ce patrimoine”, estime Fulup Jakez, le directeur de l'office public de la langue bretonne.

“Since regional languages are part of France's heritage, the consequences should instead be drawn. However, by banning the Breton tilde [the sign above the n in “Fañch”], “the 2014 circular [giving a restricted list of the diacritical marks – à, ç, ï, etc – permitted by the French civil registry] causes a degradation of this heritage,” – Executive Director of the Public Bureau for Breton Language Fulup Jakez said.

Politics, particularly the economic dimension, are also part of the local and national vision of patrimoine. Perhaps it makes sense then that controversy is never far away. French President Emmanuel Macron recently entrusted the TV host—and Marcon family friend—Stephane Bern with the “mission” to preserve endangered local heritage. The problem? Here's how historian Nicolas Offenstadt put it in a public statement, underscoring what he saw as the main issue:

Stéphane Bern ne s'est jamais caché. Il a toujours indiqué qu'il aimait ‘l'ordre et la monarchie’, et qu'il était partisan du ‘roman national’, qui n'est rien d'autre qu'une fiction identitaire faite de héros et d'épisodes forts mais idéalisés. Sa vision de l'histoire et du patrimoine est donc une vision étriquée et orientée.

Stéphane Bern never hid his fondness of ‘order and monarchy’, nor that he was in favor of a ‘national storytelling’, which is nothing else then an identity fiction made of heroes and strong but idealized episoes. His vision of history and heritage is thus a narrow and oriented vision.

That heritage often creates a tension between memory of the past and future grounding of the country—whether for economic or cultural reasons—invokes all sorts of moral arguments. In some cases, there is an added ecological frame:

- PAS-DE-CALAIS: CONTROVERSIAL WINDMILL PROJECT ENCROACHES ON A WWI MEMORIAL SITE (Pas-de-Calais: Quand un projet d'éoliennes empiète sur un lieu de mémoire de la Guerre 14-18)

20 Minutes Lille, 8 September

The town council of a small community in the Pas-de-Calais is resisting the installation of wind turbines on a former battlefield that has become a place of memory for Australians (…)

The notion of patrimoine is associated with a lot of tension is some corners of France. Consider Calais, which is grappling with an economy weakened by the migratory pressure weighing on the harbor city's attractiveness to both the transportation and tourism industries. But heritage could also be a path towards future solidarity. If you consider the spirit of “innovation” to be among Calais's traditions, you could instead respond in the same way as Martin Malvy, president of the non-profit Sites et Cités remarquables de France (Outstanding Sites and Cities of France):

« Si nous pouvons à travers la culture, changer l’image qui est celle de Calais dans les médias, alors nous aurons démontré que le patrimoine peut être un agent de solidarité efficace »

“If we are able through culture to change the image of Calais in the media, then we will have shown that heritage can be an effective agent of solidarity“